Inanna, Ishtar

Inanna for the Sumerians or Ishtar for the Akkadians is one of the most significant and complex deities in the Mesopotamian pantheon, regarded as the most important goddess. She embodies both sexual love and warfare and is also associated with the planet Venus, the morning and evening star. Inanna-Ishtar’s characteristics are often paradoxical: she can be depicted as a young, coy woman under patriarchal authority in some Sumerian poems, while in other myths, she is portrayed as an ambitious deity seeking to expand her influence, such as in Inanna and Enki and Inanna’s Descent to the Netherworld. Inanna’s marriage to Dumuzi is typically arranged by her family, reflecting her initially limited agency, though she later actively pursues Dumuzi.

In the Epic of Gilgamesh, Ishtar takes on a different persona, depicted as a femme fatale whose advances are rejected by the hero Gilgamesh, who criticizes her past treatment of lovers. This portrayal contrasts with earlier Sumerian poems, where Inanna is depicted as equally passionate but within a more controlled context. Despite these variations, her sexuality remains a central aspect of her character, whether it is expressed in youthful longing or aggressive pursuit. As a result, she was often invoked in matters related to love, sexuality, and fertility, including issues of impotence or unrequited love. Inanna-Ishtar was also considered the patron goddess of prostitutes.

As a goddess of war, Inanna-Ishtar relishes battle, often described as finding it akin to a feast. Her warlike nature is particularly emphasized in politically charged contexts, where she is associated with royal power and military might. This aspect became more pronounced during the Old Akkadian period when she was invoked by rulers like Naram-Sin as “warlike Ishtar.” In the Neo-Assyrian Empire, Ishtar of Nineveh and Ishtar of Arbela were considered distinct goddesses, each closely linked to the king and the state. In her warrior form, she is depicted with masculine characteristics, complementing her role as a powerful legitimizer of political authority.

Inanna-Ishtar’s influence in political legitimization extended to her feminine attributes as well. The “sacred marriage” ceremony symbolized the union between Inanna (represented by a high priestess) and Dumuzi (represented by the king) during the New Year festival, intended to ensure prosperity and abundance. This ritual, practiced during the late third and early second millennia BCE, was likely more symbolic than literal but emphasized the relationship between the king and the divine realm. Inanna’s role in royal inscriptions and hymns as the spouse of rulers further underscores her significant influence in the political sphere.

In her astral aspect, Inanna-Ishtar is associated with the movements of the planet Venus. Myths like Inanna and Shu-kale-tuda, where she seeks revenge after being violated by a gardener boy, have been interpreted as symbolic of Venus’s celestial course. Similarly, Inanna and Enki, which describes the goddess’s journey from Uruk to Eridu and back, mirrors Venus’s movements and may have been physically reenacted in festivals.

Inanna-Ishtar also plays a key role as a liminal figure, symbolizing transitions between life and death. Her descent to the underworld, recounted in Inanna’s Descent to the Netherworld, showcases her as a goddess who experiences death and resurrection. During this journey, she confronts her sister, Ereshkigal, the queen of the netherworld, and is turned into a corpse. Only through the efforts of her minister Ninshubur, who secures help from Enki-Ea, is Inanna revived and able to return to the world of the living. In the myth Inanna and Enki, she takes the MEs, including those associated with the underworld, further solidifying her role as a deity of transitions.

The genealogy of Inanna-Ishtar varies across traditions. In Sumerian accounts, she is usually the daughter of Nannar-Sin and Ningal and the sister of Utu-Shamash. In other traditions, she is considered the daughter of Anu or Enki. Inanna-Ishtar has an ambivalent relationship with her lover Dumuzi-Tammuz, whom she eventually condemns to the underworld. In Assyrian traditions, Ishtar of Nineveh and Ishtar of Arbela are distinct deities. During this period, she is also associated with Asshur and is sometimes referred to as Mulliltu.

The primary cult center of Inanna-Ishtar was Uruk, but she had temples in numerous cities, including Adab, Akkad, Babylon, Badtibira, Lagash, and Ur. Inanna is consistently ranked among the top deities in Mesopotamian god lists from the Early Dynastic period onward, maintaining her significance through the first millennium, especially as a national deity in the Assyrian Empire.

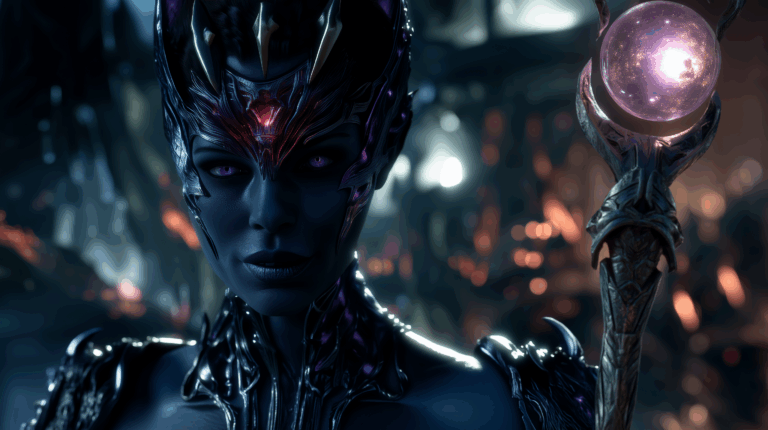

The iconography of Inanna-Ishtar is as diverse as her character. In early representations, she is symbolized by a reed bundle or gatepost, which is also used to write her name in ancient texts. The Uruk Vase shows her standing in anthropomorphic form between two gateposts. As a goddess of sexual love, she is often depicted nude, while as a warrior deity, she appears with weapons, often adorned with a beard to emphasize her masculinity. Her attribute animal is the lion, and she is frequently portrayed standing or placing a foot on its back. Her astral symbol is the eight-pointed star, with red, carnelian, blue, and lapis lazuli colors representing her contrasting feminine and masculine sides.

The Sumerian name Inanna is typically interpreted as nin.an.a(k), meaning “Lady of the Heavens,” though some interpretations translate it as “Lady of the Date Clusters.” The Semitic name Ishtar originally referred to a separate goddess who was later merged with Inanna. The etymology of Ishtar is unclear.

Many scholars say that the name of Ishtar later appeared in different forms in various cultures and was venerated across many cultures on Earth. Her name transformed from Ishtar, Ester, Astarte, Eostre, Astaroth, Ostara, and eventually became the Roman goddess of love, Venus, revered as the morning star. It’s for Astarte that Easter eggs are painted, and she is the one who resurrects after descending into the underworld.

According to Sitchin

Inanna, known later as Ishtar in Akkadian tradition, is one of the most complex and powerful figures among the Anunnaki. She is described as the daughter of Nannar (Sin) and Ningal, making her the granddaughter of Enlil and a niece to Utu (Shamash). As such, Inanna belongs to the Enlilite lineage, though her path is defined more by ambition, charisma, and sheer will than by birthright alone.

In the Anunnaki narrative, Inanna is portrayed as the goddess of love, fertility, war, and political power—a combination that reveals her dual nature as both a nurturer and a fierce warrior. Her beauty, intelligence, and seductive strength made her an unmatched figure among gods and mortals alike. Yet she is also deeply strategic, seeking dominion not only over matters of the heart but also over the structures of power on Earth.

One of her most famous acts, according to Sumerian and Akkadian texts interpreted by Sitchin, is her descent into the underworld. In this myth, Inanna challenges the laws of death by venturing into the realm ruled by her sister-in-law Ereshkigal. There, she is judged, stripped of her powers, and killed—only to be later revived and returned to the world of the living. This journey is seen as symbolic of death and rebirth, transformation, and the cost of divine ambition.

Inanna is also recognized for her role in the power struggles among the Anunnaki. She sought control over the region of Sumer, and according to Sitchin, even desired access to the ME tablets—sacred codes of civilization and technology that were in Enki’s possession. Her attempts to consolidate power included manipulating royal bloodlines, engaging in political alliances, and even confronting other Anunnaki directly.

In matters of love, her relationship with Dumuzi, son of Enki, is central to her story. Their union is passionate but tragic, ending in betrayal and sorrow, ultimately tied to the myth of seasonal death and renewal.

According to the Anunnaki theory, Inanna’s technological and military ambitions extended even into space. Sitchin suggests that she had access to advanced flight technology and that her divine chariot was not symbolic, but an actual flying craft, used in her operations across Mesopotamian territories and beyond.

In the grand structure of the Anunnaki pantheon, Inanna stands out not just as a goddess, but as a rising force—a symbol of disruption, erotic power, divine justice, and ambition. She embodies the unpredictable energy of transformation and asserts that divine femininity is as commanding as it is creative.