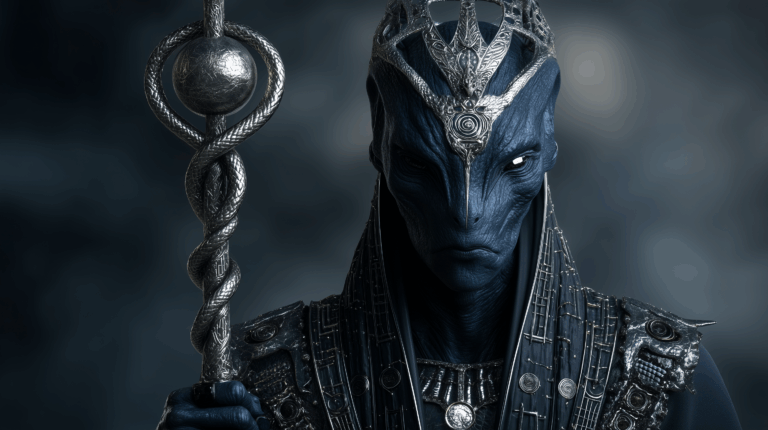

Ningishzidda

Ningishzidda, often identified with the Egyptian deity Thoth, is described in the Anunnaki narrative as the second son of Enki, born to a different mother than Marduk. This makes him a half-brother of Marduk and a direct descendant of the Enkiite lineage. He is regarded as one of the most intellectually gifted among the Anunnaki, embodying the roles of scientist, geneticist, and keeper of divine knowledge.

In Sitchin’s reconstruction of Mesopotamian and Egyptian texts, Ningishzidda plays a central role in the creation of humanity. Alongside Enki and Ninmah, he participates in the genetic engineering process that results in the formation of the Adamu—the prototype of Homo sapiens—designed as a laborer to relieve the Anunnaki of their workload on Earth. His deep understanding of genetics, biology, and complex systems earns him the title of “Lord of the Tree of Life”, a symbolic expression of his connection to DNA and life-coding.

Ningishzidda is also portrayed as the architect of the ancient ziggurats and sacred temples in Sumer, and, according to Sitchin, as one of the masterminds behind the construction of the Great Pyramid of Giza. In this interpretation, his mastery of geometry, astronomy, and advanced technologies enabled him to align monumental structures with celestial bodies, embedding astronomical knowledge into stone.

When Marduk’s political ambitions begin to challenge the Enlilite hierarchy, Ningishzidda becomes a rival to his half-brother, especially in Egypt. After serving loyally as a ruler and guide in that land under the name Thoth, he is eventually expelled by Marduk, who assumes dominance under the name Ra. This exile leads Ningishzidda to travel to other parts of the Earth. Sitchin suggests that he later reached Mesoamerica, where he was revered as Quetzalcoatl, the feathered serpent deity of knowledge and civilization.

His symbolism—a serpent intertwined with wisdom and healing—has been linked to the double helix structure of DNA, further reinforcing his role as a life-scientist. Ningishzidda stands apart from many other Anunnaki not through war or conquest, but through sacred knowledge, peaceful guidance, and devotion to truth.

Despite being displaced politically, Ningishzidda maintains an enduring legacy through his influence on priesthoods, science, and sacred architecture across the ancient world. In both Sumerian and later esoteric traditions, he is revered as a guardian of secret knowledge and a divine intermediary between gods and mortals.

His legacy is one of balance, enlightenment, and hidden wisdom, making him one of the most complex and spiritually significant figures in the Anunnaki pantheon.

There is a significant divergence between the Ningishzidda we know through Zecharia Sitchin’s theory and other popular concepts, and the one that can be understood through the study of Mesopotamian tablets and academic sources. According to academic sources, Ningishzidda is the son of Ninazu, and like him, is a chthonic deity associated with vegetation, growth, decay, snakes, and demons. His name, which translates to “Lord of the true tree,” reflects his connection to agriculture and the cycles of life and death. Descriptions of Ningishzidda highlight his role as the “Lord of pastures and fields” and liken him to “fresh grass,” underscoring his influence over plant life and harvests. He is closely linked to the vine and associated with wine and beer, as indicated in Ur texts that connect him to the é-geshtin which mens “wine-house” and to the beer deities Sirish and Ninkasi. He also holds the title “Lord of the innkeepers,” aligning with his agricultural significance.

As a chthonic deity, Ningishzidda’s myths often involve his journey to the underworld, representing the seasonal decline of vegetation from mid-summer to mid-winter. This cyclical descent is depicted in Sumerian and Akkadian myths, including Ningishzidda’s Journey to the Netherworld. In the Adapa legend, he is one of the two deities who vanish from the land, further emphasizing his role in the natural cycle of decay and rebirth.

Ningishzidda’s underworld associations are evident in his title gishgu-za-lá-kur-ra, meaning “chair-bearer of the netherworld.” He stands at the entrance of the underworld alongside Pedu, the chief gatekeeper. Rituals from the Ur and Old Babylonian periods link Ningishzidda to royal laments, as seen in The Death of Ur-Namma. By the Neo-Assyrian period, he was associated with punishment, pestilence, and disease, sometimes earning the title “Lord of the netherworld.” His involvement in incantations primarily relates to vegetation and underworld themes, reinforcing his dual role as both a life-giver and a guardian of the dead.

Ningishzidda, like Ninazu, is symbolized by the mushussu dragon and the snake. He is described as mush-mah, or the “great serpent,” and associated with the Hydra constellation in Mesopotamian astronomy. He is also depicted as a warrior god, with titles such as d-gúd-me-lám which means “warrior of splendor”, and is symbolized by the sickle sword known as pāshtu, emphasizing his role in both agriculture and warfare. Ningishzidda’s association with law, both on earth and in the underworld, reflects his reputation as a fair and reliable deity, evident from Neo-Babylonian personal names that include the phrase “Ningishzidda is judge.”

In terms of divine genealogy, Ningishzidda is the son of Ninazu and Ningirida. Gudea Cylinder B describes him as the “progeny of An,” following a divine sequence of An, Enlil, Ninazu, Ningishzidda. His wife is usually Ninazimua which translates to “the Lady who lets the good juice grow,” though in Lagash, he is paired with Geshtinanna, the goddess of dreams.

Ningishzidda’s main cult center was Gishbanda, located near Ur, where his temple was called kur-a-še-er-ra-ka, known as “mountain of lament.” After the discontinuation of his cult in Gishbanda, it may have moved to Ur, where he had a shrine within the temple of Nannar and his own “House of Justice” (é-níg-gi-na). Other centers of worship included Eshnunna (modern Tell Asmar), Lagash, Isin, Larsa, Babylon, and Uruk. In Lagash, Gudea, the ruler, built a temple for Ningishzidda and erected statues to honor him.

Ningishzidda is first mentioned in the Fara god list from the Early Dynastic III period between 2600 and 2350 BCE and remained venerated into the first millennium BCE, as indicated by his inclusion in Neo-Babylonian personal names. He received offerings in Girsu during the Ur III period, with a festival dedicated to him in the third month of the year. Limited evidence of his worship exists during the Old Babylonian period, with sparse attestations in personal names of the third and second millennia.

His name, typically rendered as d-nin-gish-zi-da, has alternate forms such as Niggissida or Nikkissida. In the Emesal dialect, he is known as Umun-muzzida. Other epithets include dgishbànda, meaning “Little Tree,” emphasizing his role as a deity of growth, renewal, and the natural decay that follows.

Iconographically, Ningishzidda is represented with snakes and the mushushu dragons, sometimes depicted emerging from his shoulders, as seen on Gudea’s seal. Cylinder seals from the Ur III period often portray him with serpents, reinforcing his chthonic nature and role as an intermediary between the living and the dead. Those who watched the introductory video in this series know that Marduk is also associated with the mushushu symbolism. In my view, this is the main reason why some researchers, like Zecharia Sitchin, linked Ningishzidda to Enki’s clan. However, as we previously discussed, academic sources trace Ningishzidda’s genealogy to Enlil’s clan, not Enki’s.

Those who follow this channel know that my aim here is to bring knowledge, so that each of you can decide what resonates best with your beliefs.

As we have seen, the tree is connected to Ningishzidda, who is also linked to the serpent, as is Marduk. According to Sitchin’s conclusions, Ningishzidda in Egypt is the same deity as Thoth. In this case, Enki, as Ptah, would be Thoth’s father, which contradicts what we know about Thoth from Egyptian mythology. The Egyptian god Thoth is associated with the Greek god Hermes, the “thrice great” Hermes Trismegistus, who brought hidden knowledge and wisdom to humanity, such as Hermeticism and Alchemy. However, it’s essential to note that, academically, Thoth and Hermes are connected, but there is no direct academic link to Ningishzidda.

Nevertheless, considering the Anunnaki history, Sitchin interprets Enki as Ptah, Marduk as Ra, and Ningishzidda as Thoth, associating them with the serpent clan, along with another of his sons, according to Sitchin’s conclusions: the enigmatic figure of the shepherd Dumuzi.