Nannar, Nanna, Sin

Nannar, also known as Su’en or Sin in Akkadian, is the Mesopotamian moon god revered as the tutelary deity of the city of Ur. Beyond his local ties, Nannar’s influence extended across the broader Mesopotamian pantheon, making him one of the major deities in the ancient world. His presence is noted in early god lists, such as the Fara god list, where he ranks alongside prominent deities like An, Enlil, Inana, and Enki. His significance is further emphasized in texts like Nanna-Suen’s Journey to Nippur, where he presents the “first fruit offerings” to Enlil, highlighting his reverential role within the pantheon.

The crescent moon serves as Nannar’s primary symbol, derived from the visual similarity between the waxing crescent and a bull’s horns. This association positions Nannar as a cowherd deity, best exemplified in The Herds of Nanna, which details his relationship with cattle. His role as a fertility god is also linked to the lunar cycle, which mirrors the menstrual cycle. This connection is evident in birth-related rituals like A Cow of Sin, where Nannar aids in easing the labor pains of a pregnant cow named Geme-Sin.

Nannar’s celestial attributes are frequently described in terms of radiance and brilliance, with significant attention given to his lunar cycle, which ancient Mesopotamians meticulously observed for omens. His association with divination is prominent in Akkadian literature, where Nannar is praised for his ability to illuminate darkness and reveal hidden truths. In his judicial role, he is often paired with the sun god Shamash, as both deities are involved in issuing decrees, determining destinies, and overseeing divine justice.

In the myth Enlil and Ninlil, Nannar is depicted as the firstborn son of Enlil and Ninlil, with three brothers: Nergal-Meslamtaea, Ninazu, and Enbililu. This filial connection underscores Nannar’s prominence, particularly during the Ur III period, when Ur was a significant political and religious center. Occasionally, Nannar is also portrayed as a child of An, symbolizing An’s broader role as the father of all gods.

Nannar’s consort is the goddess Ningal (known as Nikkal in Akkadian), with whom he fathered Inanna and Utu, key figures in Mesopotamian mythology. Other children attributed to Nannar include Ningublaga, Amarra-azu, Amarra-he’ea, and Numušda. His later connection with Nuska, a vizier of Enlil, suggests potential syncretism influenced by Aramaic beliefs, particularly in Harran.

Nannar’s primary cult center was in Ur, where the ziggurat, built by Ur-Nammu, was dedicated to him. The temple, called é-kish-nu-gál which means “House of Great Light”, had counterparts in Babylon and Nippur, reflecting his broader influence. Harran was another significant site of worship, with the temple é-húl-húl meaning “House of Rejoicing” serving as a major center from the Old Babylonian period onward. His worship spread to regions like Ga’esh and Urum (modern Tell `Uqair), highlighting his widespread presence in ancient religious practices.

Nannar’s name is intricately linked with the number 30, symbolizing the 30-day lunar month. The number represents the full lunar cycle, reinforcing Nannar’s deep connection to the measurement of time and the celestial order, further demonstrating his role as a regulator of both divine and human affairs.

Interestingly, Nannar was the primary deity of Ur during the era traditionally associated with the patriarch Abraham, who is said to have originated from this city. This raises intriguing questions about the possible interactions between Abraham and the worship of Nannar. Could Abraham, a monotheistic figure in biblical tradition, have been familiar with Nannar’s cult? The symbolism of the crescent moon, prominent in both Nannar’s iconography and the later emergence of Islam, adds a layer of potential continuity. Islam’s crescent moon symbol and its connection to the god revealed to the Prophet Muhammad prompts deeper speculation: Was it a mere coincidence that a deity worshipped during Abraham’s time in the same region later appeared with similar lunar symbolism in another monotheistic faith?

Further adding to Nannar’s legacy is the naming of the Sinai Peninsula, which is thought to honor the deity Sin, Nannar’s Akkadian name. The region’s historical name suggests enduring reverence for the moon god, reinforcing his deep cultural and geographical impact across centuries.

Both Nannar and Enki share connections with the crescent moon, although Enki’s association is more symbolic, linked to his dominion over the waters beneath the earth. This shared lunar imagery could reflect deeper symbolic meanings related to wisdom, fertility, and the cycles of nature, demonstrating the complex interplay of celestial and terrestrial themes in Mesopotamian religion.

Nannar’s enduring legacy as a deity of illumination, fertility, divination, and justice places him at the center of both daily life and broader cosmic frameworks across ancient Mesopotamia. His possible connections to later religious developments invite contemplation of his long-standing influence and the overlapping symbols of monotheism, lunar worship, and divine justice.

Nannar, known as Sin in Akkadian texts, is the firstborn son of Enlil and Ninlil. His birth occurs after Enlil’s banishment to the Ekur due to a transgression, and his union with Ninlil in exile gives rise to Nannar, who becomes one of the most significant Anunnaki deities governing early human civilization.

According to the Anunnaki theory, Nannar is appointed as the lord of the city of Ur, a major spiritual and administrative center in Sumer. Ur becomes one of the most sacred and influential cities in the Anunnaki domain, serving as a key religious capital dedicated to lunar observation and calendar systems—both deeply tied to Nannar’s role as a moon god.

As a son of Enlil and part of the Enlilite lineage, Nannar occupies a prestigious and strategic position. Unlike the warrior role taken on by his half-brother Ninurta or the storm authority given to Ishkur, Nannar’s domain is intellectual, spiritual, and symbolic. He is responsible for timekeeping, rituals, and astronomical knowledge, which are transmitted to humanity under his patronage.

Nannar is also known as the father of Utu (Shamash), the solar deity and judge, and Inanna (Ishtar), the goddess of love, war, and political power. These two offspring form one of the most active and dynamic branches of the Anunnaki hierarchy, with deep influence over human development, justice, sexuality, and royal authority. This makes Nannar the patriarch of a lineage that impacts both Anunnaki internal affairs and human civilization’s evolution.

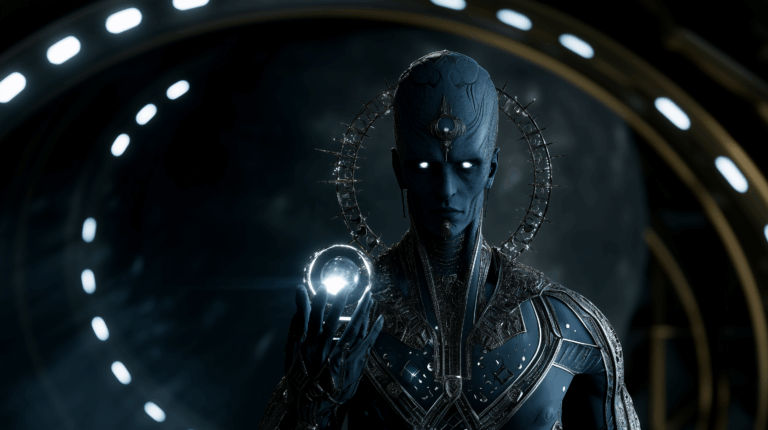

Symbolically, Nannar is depicted with a crescent moon and associated with nighttime illumination and the rhythms of agriculture and tides. In Zecharia Sitchin’s interpretation, Nannar’s power is tied not only to lunar cycles but also to Anunnaki technology, perhaps involving orbital observation platforms or lunar stations. This interpretation suggests that his divine attributes may reflect a technologically advanced lunar presence, supporting the notion that the moon played a functional role in the Anunnaki operation on Earth.

Politically, Nannar is portrayed as wise, measured, and diplomatic. While he remains loyal to the Enlilite cause, his city and followers often become entangled in the conflicts between the Enlilites and the Enkiites—especially during the rise of Marduk. During the post-diluvian era, Ur thrives under Nannar’s oversight, becoming one of the cradles of human kingship and divine law.

However, the eventual destruction of Ur—attributed in part to nuclear fallout from the conflict between Enlilites and Marduk’s forces—marks a tragic end to Nannar’s city. In Sitchin’s narrative, this destruction is lamented by the Anunnaki, and Nannar himself is portrayed as a dignified but sorrowful figure who witnesses the collapse of the civilization he nurtured.

Despite this loss, Nannar’s legacy endures through the continuation of timekeeping, astrology, and religious symbolism rooted in lunar cycles. He remains one of the most stable and enduring figures in the Anunnaki pantheon.