Ishkur, Addad, Adad

Ishkur, known as Adad in Akkadian, is the Mesopotamian storm god associated with both the life-giving and destructive aspects of rain and floods. His character embodies the ambivalence of storms, which can either benefit or devastate humanity. This dual nature is reflected in the Sumerian and Akkadian traditions, with Ishkur and Adad being seen as a warlike figure capable of unleashing nature’s fury, as well as a deity of rain who nurtures crops and promotes fertility. The differing emphasis on his roles can be attributed to regional agricultural needs: in southern Mesopotamia, he is often seen as a destructive force, while in the north, he is primarily regarded as a bringer of life-giving rains.

Ishkur’s power extends to the battlefield, with his storms symbolizing his might in war. In Sumerian hymns, he is portrayed as destroying rebellious lands, while Akkadian texts depict him as overwhelming enemies with his elemental strength. His association with justice and divination further underscores his influence, reinforcing his role as a god of order and fairness.

The genealogy of Ishku-Adad varies across traditions. He is often considered the son of An-Anu, the sky god, though Sumerian texts sometimes identify Enlil as his father. The storm god’s consorts also differ, with Medimsha recognized as Ishkur’s wife in Sumerian tradition, while Adad’s Akkadian counterpart is paired with Shala. His children, as listed in the god list An = Anum, include two sons and three daughters, though their roles and attributes remain largely unspecified.

The syncretism of Ishkur with other storm gods, such as the north Babylonian Wer, Hurrian Teshub, and Hittite-Luwian Tarhun. This deity is also identified with Baal in Canaanite texts, revealing a broader cultural connection that emphasizes his role as a central storm god across the Near East. This merging of deities likely facilitated the spread of Adad’s cult throughout Mesopotamia and beyond.

Ishkur-Adad’s main cult centers spanned Mesopotamia, with the temple é-u-gal-gal-la which means “House of Great Storms” in Karkar serving as an early site of worship. In Babylon, his temple was known as the “House of Abundance,” and he had sanctuaries in other major cities, including Sippar, Nippur, Ur, and Uruk. In Assur, the “House which Hears Prayers” was transformed into a double temple for Adad and Anu by King Shamshi-Adad I, illustrating his prominence in Assyrian worship. Adad’s main cult center during the Neo-Assyrian period was at Kurbaʾil, though temples dedicated to him existed throughout Assyrian cities like Kalhu and Nineveh.

The earliest attestations of Ishkur date back to the mid-third millennium BCE, appearing in god lists and cult sites like Lagash and Adab. By the Old Babylonian period, Ishkur-Adad had become one of the “great gods” of the Babylonian pantheon, revered for both his creative and destructive powers. Texts like Enki and the World Order praise him as the “bringer of plenty,” while the Atrahasis epic emphasizes his destructive potential, depicting Adad as the force behind droughts, famine, and the Great Flood intended to annihilate humanity.

In Assyria, Adad held a high rank among the gods, evident from the royal inscriptions that regularly invoke his favor. For instance, Ashurnasirpal II refers to himself as “beloved of Adad, who is almighty among the gods.” Even as Babylonian religion evolved, Adad continued to receive worship, maintaining a presence in major cities into the Hellenistic period.

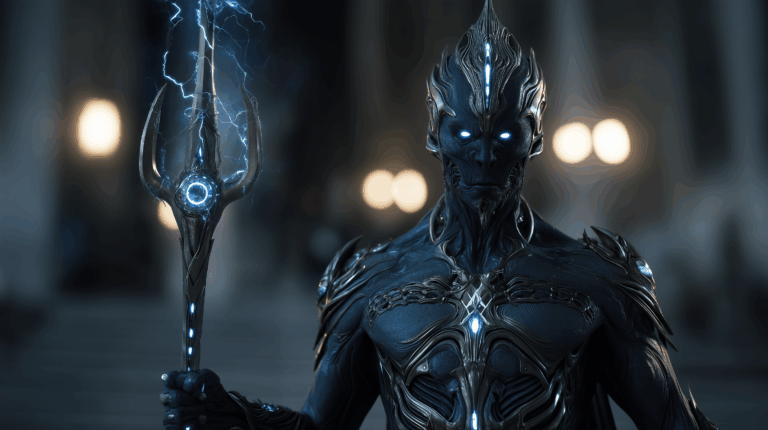

Iconographically, Ishkur-Adad is depicted wielding lightning bolts and standing on or beside a bull or lion-dragon. The lion-dragon symbol, common in early art, was later complemented by the bull, which became more prevalent from the Ur III period onwards. His name in Sumerian, represented by the sign for “wind,” remains enigmatic, while the Akkadian Adad derives from the Semitic root hdd, meaning “to thunder.”

The enduring legacy of Ishkur-Adad lies in his embodiment of the storm’s dual nature—both as a force of nourishment and as a bringer of devastation—mirroring the unpredictable power of the natural world. His influence extended into divination, justice, and warfare, making him a multifaceted deity whose presence was felt across the spectrum of Mesopotamian life and beyond.

Ishkur, known as Adad in Akkadian, is the youngest son of Enlil, born through Enlil’s relationship with a concubine rather than his official consort Ninlil. As a result, Ishkur does not inherit the same political prestige as his half-brother Ninurta, but he nonetheless occupies a respected and active role within the Enlilite faction of the Anunnaki pantheon.

In the Anunnaki theory, Ishkur is described as a fierce and unpredictable deity associated with storms, thunder, and weather phenomena. His domain is not only celestial but also terrestrial, particularly in the mountainous regions and western territories beyond the core Sumerian cities. He is often sent to oversee or control the more remote outposts of the Anunnaki dominion—especially those dealing with humans in the less-developed zones.

Ishkur is granted authority over the regions that later become the lands of Canaan and Lebanon. In this capacity, he plays a crucial role as a regional administrator and weather-controlling deity. His violent storms, torrential rains, and symbolic power over fertility and destruction earn him the reputation of both a bringer of blessings and a feared punisher of disobedience.

One of Ishkur’s most significant actions in the Anunnaki timeline is his alignment with the Enlilite cause during the escalating conflict with the Enkiite faction—especially during the power struggle between Enlil’s lineage and the rise of Marduk. Ishkur becomes a reliable ally in the battles that precede the cataclysmic wars and the eventual fallout following the destruction caused by nuclear weapons in the Near East.

Though never positioned as a central political leader, Ishkur’s power lies in his command of nature and his influence over crucial geographical areas. His symbolic number is six, reflecting a role of action and energy rather than governance. In mythological texts, he is depicted wielding thunderbolts and riding storm clouds—an image echoed in Sitchin’s interpretations, where Ishkur’s control over weather is seen as technologically based, possibly involving atmospheric manipulation devices.

His biblical and mythological echoes appear in figures such as Baal (in Canaanite tradition), where he retains the attributes of a storm god wielding elemental forces. Ishkur’s hybrid status—neither fully of royal blood nor an outsider—allows him to move dynamically within Anunnaki politics, serving as an enforcer, a punisher, and at times, a protector.

In the final phases of the Anunnaki presence on Earth, Ishkur’s territories become central to later human narratives and religious developments, suggesting that his cult and memory endured even as other Anunnaki figures faded into obscurity.